The Long View- Beyond the Mattole Clearcut Wars, a Choice of Futures

[note: though written in spring 2001, this writing is just as applicable and relevent today, though the 3,000 acres of oldgrowth forest he mentions now stands at around 2,000. There wouldn't be that much left if not for the efforts and dedication of community members and volunteers working through the legal system and taking action in the woods.]

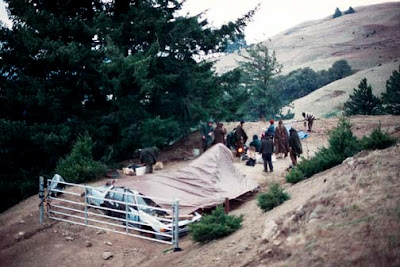

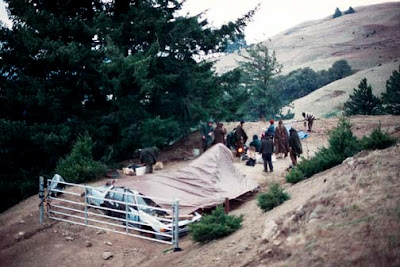

photo: MWD

by Freeman House 2001

This forest is not dark, but broken by large, bright sweeps of upland prairie that now, in the spring of 2001, are as radiantly green as any mythical image of the welcoming land. This country has been sacred ground and tribal territory, milk and honey, meat and wood, garden and factory, and now the last stand in defense of a legacy landscape, depending on whose eyes have been looking. Its current owner is Maxxam Corporation, a conglomerate renowned for its devotion to the bottom line.

When you're among the old trees on Rainbow Ridge, the prairie expanses are never far from sight or out of mind. The big trees are Douglas firs, four feet through at the base, large before any white immigrant ever saw them. There are tanoaks and madrones and coast live oaks, too, giants of their own races.

photo: MWD

A century and a half ago, there was a lot of this kind of habitat in the Coast Range; now this 3,000 acres of low-elevation, mixed-conifer forest and coastal prairie is the largest uninterrupted piece of its type left in California. Dependent wildlife, once plentiful across the landscape, has fled here for shelter. If you're in the right place, your eye is drawn to the long view, all the way to the silver glare of the Pacific. We're in the headwaters of the largest tributary of the Mattole River, and up here at 1,500 to 2,000 feet above sea level the creeks run clear and abundant. Farther downstream, where the big trees have been cut too close to the streams, the picture is not so pretty.

photo: MWD

In a place like this, where the vistas are at the same time grand and softly inviting, the mind can be drawn back to the time before the forest was owned by Maxxam, and forward to when Maxxam itself will be history, to deep time and large cycles. Also to what was once called the sublime, especially here where an earthquake can lift up the land several feet in a few seconds, where more rain falls in the five-month wet season than in most places in California. Such landscapes invite philosophy, as they come to represent nature's living memory. Once they're gone, we will not be able to re-imagine their elegant complexities. The highest and best use of these rich places may be as an arena for reconsideration of our human place and function in the landscape.

Once we get beyond the habit of regarding the landscape as a static event, we'll be closer to ordering our lives within the constraints and opportunities of our unique habitat-homes. Not only does the landscape change over time, but so do the social values that drive our activities on the land. Our activities on the land are as large a determinant of how that land functions as are soil types, weather cycles, and geology. In North America, we're running out of time to rediscover the nature of our relationships to its places, to begin living as if we were going to be here for a while. In the Mattole watershed, the westernmost in California, it doesn't seem strange to think like this. After all, the current dominant culture has been here for less than a century and a half.

One ridgeline west of where the forest is being clearcut, but still on Maxxam land, there is an unusual sight: a garden-sized stand of coast live oaks, very old. In a forest type identified by its mix of species, it is rare to find a pure stand of any one of them. But it is likely that two hundred years ago many such small stands dotted the Mattole landscape. The native peoples (Mattole, Sinkyone, Wailaki, and Wiyot) relationship to the oak was complex and active, productive oak groves maintained by family right and responsibility. The timely use of fire optimized acorn production, arrested the growth of competing species, and controlled pests. The results of such management were likely many well-tended groves throughout the Mattole (especially tanoaks, treasured for their large, sweet nut), maintained at an arrested stage of natural succession.

Annual first salmon and first acorn ceremonies reinforced the human population's sense of its place within ecosystem processes and provided a way for tribal knowledge to incorporate an ever-widening range of experience.

photo: MWD

As a result, core resources were managed for the security of future generations with a style of cultivation and consumption likely to result in more food rather than less.

The Euro-Americans who invaded the valley beginning in 1856 had little time to learn about indigenous land management. Within seven years of settlement the last natives were being rounded up and forcibly moved to distant reservations.

The quarter of the watershed landscape occupied by coastal prairie plant communities was pushed to support a smaller human population who had to work harder to survive than the peoples they had replaced. Subsistence gardening on the fertile bottomlands was augmented with the cash from cattle and dairy products. Grass seeds carried in the animals hooves quickly replaced the perennial bunchgrasses which had fed browsers like deer and elk year-round, with European annuals, green and nutritious in the late winter and spring only. The bottomland was put to work producing hay for cattle rather than grains and vegetables for humans. The cash economy had come to the table. The more it eats, the hungrier it grows.

BOOM: Oil and Leather

Euro-Americans seem to be natural entrepreneurs, always responding inventively to cash shortages. Beginning in 1864, oil seeps in the foothills seemed to some like they might solve the problem forever. But although the oil came out of the ground so clean that it could be burned in lamps, it came in small quantities. Before the combustion engine, the fuel was worth hauling out in goatskin sacks on the backs of mules, but it soon became uneconomical.

In the 1880s , another generation discovered that the ubiquitous tanoak, once prized as food, had a high concentration of tannin in its bark that made it useful in the leather tanning process. There was enough to make it seem like one more inexhaustible resource of the Wild West. So much that it financed the construction of a reduction plant in nearby Briceland that processed 3,000 cords of bark a year. At the mouth of the river, two miles of rail were laid and a quarter-mile of wharf built out into some of the windiest waters in the Pacific to carry the bark out of the hills and down to San Francisco. Another wharf was built at Shelter Cove, near the headwaters of the river. The ocean took out the wharf at the mouth five years later, but the tanbark lasted long enough to support crews living in the woods for six to ten weeks every spring for twenty years, until the war to end all wars. The crews would fell the trees, strip the bark, and leave the wood on the ground. And then it was gone, or so scarce as to be unrewarding to go out and get it.

It would be another generation before the stump-sprouted shoots were large enough to be called trees, and by that time synthetic tannins would be doing the job. A little more than 50 years had passed between the time those tanoak groves were providing staple acorns to several thousand humans and the time they were lying naked on the hillsides. This would not be the last time the cash economy would turn natural provision upside down.

photo: MWD

BUST: Eating Venison

The next generation had a quiet time that would be remembered as a sort of hardscrabble utopia by its survivors. A road to the county seat got built and the produce of orchards and dairies could be hauled into town to supplement an economy based as much on mutual aid as on competition. King cash was in charge now, its hold cemented by gasoline, but it was so far ruling with a gentle hand. The watershed would no longer provide for as many people, but it still provided well. Lean times meant eating more venison and salmon: who could complain? The quarter of the watershed landscape in prairie and pasture was doing all the work; the dark forests were too far from the mills and situated on slopes too steep to engage the economic imagination.

BOOM: Falling Timber

The next war changed all that. Or rather, the events after the war did so. The wartime meat subsidies that sweetened the pot for ranchers were soured by a tax on their standing timber, which occupies three-quarters of the watershed. As the US armed forces returned from World War II, they created a housing boom which in turn created an enormous demand for Douglas-fir two-by-fours for mass-produced tract housing. The war effort had resulted in the improvement of heavy machinery that ran on treads. Small tractors capable of navigating steep slopes, cutting roads, and hauling logs made the previously inaccessible back country of the Coast Range vulnerable. In Humboldt County, the tax on standing timber remained until the late 60s, so there was every incentive for the independent landowner to log.

Small land-based timber corporations began to acquire large parcels of remote timberlands. An industry that had focused on redwood now spread to every softwood-rich habitat in the West. The flurry of growth included Pacific Lumber Company (PL), previously devoted almost exclusively to redwood lumber production. Locally owned and paternalistic, PL ran its operations as if its company town at Scotia would support many generations.

In California, there was little timber regulation until 1975. In a quarter century, some 90% of the Mattole watershedÕs ancient Douglas-fir forests was logged Ã& much of it by gyppo (independent) outfits contracted by resident ranchers Ã& with no replanting required. Never had so much soil been exposed to direct pounding by the regionÕs heavy rainfall. Spiderwebs of abandoned dirt roads criss-crossed the landscape Ã& ten linear miles for every square mile, on average. Although several mills hired valley men for 20 years, more of the revenue represented by the timber was leaving the watershed for mills in other parts of the state.

The cash economy was turning the region into a cash colony.

photo: MWD

BUST: Mud

In 1955, and again in 1964, "hundred-year" storms occurred late in the winter. The winter of 1955 had been cold, and there was an unusually heavy snow pack on the higher hills. When the snow was melted by rain, it unleashed enormous amounts of water down gullies, ravines, and feeder creeks that no longer had vegetation to slow it down and trap some of the soil it carried. In a matter of days, the nature of the river was changed Ã& from a stable, cool, and deeply channeled watercourse to one that rose and fell flashily, meandering in its newly shallowed channel and tearing out streamside vegetation. Sediment jammed river bottom gravels and filled pools once deep enough to remain cool all summer. Clean gravels and cool waters are an absolute requirement of salmon; a precipitous decline in salmon populations followed, and continued until 1990. The hotter, south-facing slopes, unplanted after logging, often came back in thick chaparral, prone to burn uncontrollably.

REHABILITATION

Windfall profits, along with the ugliness of a ravaged landscape, may have moved some ranchers to sell out. It took only the subdivision of a few of the large, cut-over ranches in the Mattole to turn the watershed into a destination for the thousands of young urban people seeking self-reliant lives. In the 70s, the back-to-the-land immigrations had observable effects on the landscape, but possibly more importantly, on the nature of human desire as it is directed at the landscape. Within ten years, the human population of the valley tripled. By and large, the newcomers brought with them attitudes native to the burgeoning national environmental movement, as well as the conviction that enormous social change was impending and that they were the agents of that change. Some of the first institutions they created were highly effective environmental reform organizations.

photo source

The new city-bred pioneers had their hands full staying alive for the first few years. Rapid and near-total immersion in the wilder landscape brought a humbling and visceral experience of the degree to which modern people are ignorant of the ways the natural world works. Environmental restoration projects proved to be highly effective learning forums. In the Mattole, as well as in other places in North America, a restoration movement began to take shape, a movement that emphasizes the systematic self-education of human communities about the habitats that support them.

Homesteaders who tended salmon eggs gained more intimacy with the creatures freshwater needs than any classroom training might have given. Workers replanting barren slopes with local Douglas-fir seedlings and monitoring their survival learned a generation's worth of the processes of natural succession within a few years. Nothing teaches practical hydrology more quickly than attempts to armor eroding stream banks.

Habitat rehabilitation work quickly expanded to include a more informed examination of land-use practices. Organizations like the Institute for Sustainable Forestry developed measurable standards for timber production within ecological parameters. Land trusts were established to move certain lands into the public domain and administer others through benign conservation easements. All these new organizations showered the community with educational newsletters. Collective learning of this sort had not taken the form of social institutions since the destruction of indigenous peoples rituals.

It was trial and error. Like Gil Gregori, a riverfront farmer and urban transplant who has engaged in restoring the Mattole for a quarter century, most settlers didn't arrive with the knowledge that willow plantings will attract valuable insects, shore up banks, and cost less than moving boulders. "I learned it," Gregori says. "(I saw that) they slow the water down. If you can get something to grow there, it's going to do the work for you. As the years went by, people started seeing what was working and what wasn't, which influenced not only the land but their own identity, says Gregori's partner Robie Tenorio. "The restoration feels right," she says. "It feels like you're here, and it's your connection to the land. We live on the river, and this is where we are."

Playing counterpoint to these progressive movements are the various effects of the new-age version of the cash economy- outlaw marijuana production- introduced by the newcomers, but now widespread. Early cash flow from these activities freed up volunteer time that nourished the arts and social and environmental movements. But recent innovations in bunker-style indoor growing powered by large, often unattended, generators are now able to destroy habitat with diesel spills. Community erodes as people hide their daily activities from each other, and generalized paranoia blooms in the form of locked gates and more extreme types of security.

Nonetheless, a community has responded to the land.

In 1988, the Mattole Restoration Council's survey of old growth habitat in the Mattole revealed it had been reduced by 93% since 1947. The survey also revealed that none of the remaining habitat had permanent protection.

A dramatic poster map was mailed to every one of several thousand residents and landowners in the valley. This local information moved community groups to engage in acquisition and regulatory efforts that put some two-thirds of the remaining old forests under public protection by 2000. Maxxam's three thousand acres in the North Fork are the last and most valuable legacy habitat remaining unprotected.

file photo

As I begin writing, a woman named Kim Starr has been sentenced to 120 days in the county jail for defending some of the last of the watershed that looks as it did two hundred years ago. "When that wildness is threatened," Starr said from Humboldt County Correctional Facility, "I donÕt know what else to do. All the waterways and the rolling hills and all the mosses on all the Doug fir trees and bay laurel trees and all the old-growth: That wildness gets in our hearts. It hurts knowing that 60 acres have been just totally stripped in that area."

file photo

Starr is one of several hundred forest activists and several score residents resisting Maxxam"s intention to take down this old forest in the next decade. Her sentence is stiffer because she refused probation. "I reject that system completely," said Starr, who said she wouldn't rule out more civil disobedience. "The more of us that do it, the stronger we become." The 54 people arrested for similar incidents of trespass and resisting arrest (they tend to be locked down and difficult to remove when arrested) await sentencing. Up to 200 additional "John Does" can be charged with obstructing a lawful business as part of a strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP suit) and restraining order begged and received by Pacific Lumber/Maxxam Corporation.

file photo

Two irreconcilable and very modern projections of human desire are encountering each other on these remote lands. The seemingly dominant one, supported by regulations and law, is the treatment of landscapes as sacrifice zones to what Wendell Berry calls the total economy, where there is no value but that measured in dollars. The outcome of this vector of desire is all too predictable, as can be seen in the preceding history.

Resistance to this alternative, at its finest, may be emblematic of our desire to reintegrate human communities and landscapes. Until we learn more about the land's own strategies for recovery, the results of this effort are unpredictable, but the more wild habitat we allow to be destroyed, the less likely it is to reach fruition.

The practitioners of civil disobedience are buying time for community activists to explore acquisition alternatives. By putting their lives on the line for wild, living landscapes, they lend strength to the foresters and landowners, restorationists, and environmentalists who are inventing the details of a livable future. The land demands of us that we develop a long view of the future. If that future is to include the lives of places and of communities of place, we are also required to learn the lessons of our long experience of those places, and learn them soon.

Freeman House, a resident of the Mattole River valley, is author of Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species (1999, Beacon Press, Boston).

This article first appeared in Terrain Magazine Fall 2001. Terrain is the magazine of the Berkeley Ecology Center.

photo: MWD

by Freeman House 2001

This forest is not dark, but broken by large, bright sweeps of upland prairie that now, in the spring of 2001, are as radiantly green as any mythical image of the welcoming land. This country has been sacred ground and tribal territory, milk and honey, meat and wood, garden and factory, and now the last stand in defense of a legacy landscape, depending on whose eyes have been looking. Its current owner is Maxxam Corporation, a conglomerate renowned for its devotion to the bottom line.

When you're among the old trees on Rainbow Ridge, the prairie expanses are never far from sight or out of mind. The big trees are Douglas firs, four feet through at the base, large before any white immigrant ever saw them. There are tanoaks and madrones and coast live oaks, too, giants of their own races.

photo: MWD

A century and a half ago, there was a lot of this kind of habitat in the Coast Range; now this 3,000 acres of low-elevation, mixed-conifer forest and coastal prairie is the largest uninterrupted piece of its type left in California. Dependent wildlife, once plentiful across the landscape, has fled here for shelter. If you're in the right place, your eye is drawn to the long view, all the way to the silver glare of the Pacific. We're in the headwaters of the largest tributary of the Mattole River, and up here at 1,500 to 2,000 feet above sea level the creeks run clear and abundant. Farther downstream, where the big trees have been cut too close to the streams, the picture is not so pretty.

photo: MWD

In a place like this, where the vistas are at the same time grand and softly inviting, the mind can be drawn back to the time before the forest was owned by Maxxam, and forward to when Maxxam itself will be history, to deep time and large cycles. Also to what was once called the sublime, especially here where an earthquake can lift up the land several feet in a few seconds, where more rain falls in the five-month wet season than in most places in California. Such landscapes invite philosophy, as they come to represent nature's living memory. Once they're gone, we will not be able to re-imagine their elegant complexities. The highest and best use of these rich places may be as an arena for reconsideration of our human place and function in the landscape.

Once we get beyond the habit of regarding the landscape as a static event, we'll be closer to ordering our lives within the constraints and opportunities of our unique habitat-homes. Not only does the landscape change over time, but so do the social values that drive our activities on the land. Our activities on the land are as large a determinant of how that land functions as are soil types, weather cycles, and geology. In North America, we're running out of time to rediscover the nature of our relationships to its places, to begin living as if we were going to be here for a while. In the Mattole watershed, the westernmost in California, it doesn't seem strange to think like this. After all, the current dominant culture has been here for less than a century and a half.

One ridgeline west of where the forest is being clearcut, but still on Maxxam land, there is an unusual sight: a garden-sized stand of coast live oaks, very old. In a forest type identified by its mix of species, it is rare to find a pure stand of any one of them. But it is likely that two hundred years ago many such small stands dotted the Mattole landscape. The native peoples (Mattole, Sinkyone, Wailaki, and Wiyot) relationship to the oak was complex and active, productive oak groves maintained by family right and responsibility. The timely use of fire optimized acorn production, arrested the growth of competing species, and controlled pests. The results of such management were likely many well-tended groves throughout the Mattole (especially tanoaks, treasured for their large, sweet nut), maintained at an arrested stage of natural succession.

Annual first salmon and first acorn ceremonies reinforced the human population's sense of its place within ecosystem processes and provided a way for tribal knowledge to incorporate an ever-widening range of experience.

photo: MWD

As a result, core resources were managed for the security of future generations with a style of cultivation and consumption likely to result in more food rather than less.

The Euro-Americans who invaded the valley beginning in 1856 had little time to learn about indigenous land management. Within seven years of settlement the last natives were being rounded up and forcibly moved to distant reservations.

The quarter of the watershed landscape occupied by coastal prairie plant communities was pushed to support a smaller human population who had to work harder to survive than the peoples they had replaced. Subsistence gardening on the fertile bottomlands was augmented with the cash from cattle and dairy products. Grass seeds carried in the animals hooves quickly replaced the perennial bunchgrasses which had fed browsers like deer and elk year-round, with European annuals, green and nutritious in the late winter and spring only. The bottomland was put to work producing hay for cattle rather than grains and vegetables for humans. The cash economy had come to the table. The more it eats, the hungrier it grows.

BOOM: Oil and Leather

Euro-Americans seem to be natural entrepreneurs, always responding inventively to cash shortages. Beginning in 1864, oil seeps in the foothills seemed to some like they might solve the problem forever. But although the oil came out of the ground so clean that it could be burned in lamps, it came in small quantities. Before the combustion engine, the fuel was worth hauling out in goatskin sacks on the backs of mules, but it soon became uneconomical.

In the 1880s , another generation discovered that the ubiquitous tanoak, once prized as food, had a high concentration of tannin in its bark that made it useful in the leather tanning process. There was enough to make it seem like one more inexhaustible resource of the Wild West. So much that it financed the construction of a reduction plant in nearby Briceland that processed 3,000 cords of bark a year. At the mouth of the river, two miles of rail were laid and a quarter-mile of wharf built out into some of the windiest waters in the Pacific to carry the bark out of the hills and down to San Francisco. Another wharf was built at Shelter Cove, near the headwaters of the river. The ocean took out the wharf at the mouth five years later, but the tanbark lasted long enough to support crews living in the woods for six to ten weeks every spring for twenty years, until the war to end all wars. The crews would fell the trees, strip the bark, and leave the wood on the ground. And then it was gone, or so scarce as to be unrewarding to go out and get it.

It would be another generation before the stump-sprouted shoots were large enough to be called trees, and by that time synthetic tannins would be doing the job. A little more than 50 years had passed between the time those tanoak groves were providing staple acorns to several thousand humans and the time they were lying naked on the hillsides. This would not be the last time the cash economy would turn natural provision upside down.

photo: MWD

BUST: Eating Venison

The next generation had a quiet time that would be remembered as a sort of hardscrabble utopia by its survivors. A road to the county seat got built and the produce of orchards and dairies could be hauled into town to supplement an economy based as much on mutual aid as on competition. King cash was in charge now, its hold cemented by gasoline, but it was so far ruling with a gentle hand. The watershed would no longer provide for as many people, but it still provided well. Lean times meant eating more venison and salmon: who could complain? The quarter of the watershed landscape in prairie and pasture was doing all the work; the dark forests were too far from the mills and situated on slopes too steep to engage the economic imagination.

BOOM: Falling Timber

The next war changed all that. Or rather, the events after the war did so. The wartime meat subsidies that sweetened the pot for ranchers were soured by a tax on their standing timber, which occupies three-quarters of the watershed. As the US armed forces returned from World War II, they created a housing boom which in turn created an enormous demand for Douglas-fir two-by-fours for mass-produced tract housing. The war effort had resulted in the improvement of heavy machinery that ran on treads. Small tractors capable of navigating steep slopes, cutting roads, and hauling logs made the previously inaccessible back country of the Coast Range vulnerable. In Humboldt County, the tax on standing timber remained until the late 60s, so there was every incentive for the independent landowner to log.

Small land-based timber corporations began to acquire large parcels of remote timberlands. An industry that had focused on redwood now spread to every softwood-rich habitat in the West. The flurry of growth included Pacific Lumber Company (PL), previously devoted almost exclusively to redwood lumber production. Locally owned and paternalistic, PL ran its operations as if its company town at Scotia would support many generations.

In California, there was little timber regulation until 1975. In a quarter century, some 90% of the Mattole watershedÕs ancient Douglas-fir forests was logged Ã& much of it by gyppo (independent) outfits contracted by resident ranchers Ã& with no replanting required. Never had so much soil been exposed to direct pounding by the regionÕs heavy rainfall. Spiderwebs of abandoned dirt roads criss-crossed the landscape Ã& ten linear miles for every square mile, on average. Although several mills hired valley men for 20 years, more of the revenue represented by the timber was leaving the watershed for mills in other parts of the state.

The cash economy was turning the region into a cash colony.

photo: MWD

BUST: Mud

In 1955, and again in 1964, "hundred-year" storms occurred late in the winter. The winter of 1955 had been cold, and there was an unusually heavy snow pack on the higher hills. When the snow was melted by rain, it unleashed enormous amounts of water down gullies, ravines, and feeder creeks that no longer had vegetation to slow it down and trap some of the soil it carried. In a matter of days, the nature of the river was changed Ã& from a stable, cool, and deeply channeled watercourse to one that rose and fell flashily, meandering in its newly shallowed channel and tearing out streamside vegetation. Sediment jammed river bottom gravels and filled pools once deep enough to remain cool all summer. Clean gravels and cool waters are an absolute requirement of salmon; a precipitous decline in salmon populations followed, and continued until 1990. The hotter, south-facing slopes, unplanted after logging, often came back in thick chaparral, prone to burn uncontrollably.

REHABILITATION

Windfall profits, along with the ugliness of a ravaged landscape, may have moved some ranchers to sell out. It took only the subdivision of a few of the large, cut-over ranches in the Mattole to turn the watershed into a destination for the thousands of young urban people seeking self-reliant lives. In the 70s, the back-to-the-land immigrations had observable effects on the landscape, but possibly more importantly, on the nature of human desire as it is directed at the landscape. Within ten years, the human population of the valley tripled. By and large, the newcomers brought with them attitudes native to the burgeoning national environmental movement, as well as the conviction that enormous social change was impending and that they were the agents of that change. Some of the first institutions they created were highly effective environmental reform organizations.

photo source

The new city-bred pioneers had their hands full staying alive for the first few years. Rapid and near-total immersion in the wilder landscape brought a humbling and visceral experience of the degree to which modern people are ignorant of the ways the natural world works. Environmental restoration projects proved to be highly effective learning forums. In the Mattole, as well as in other places in North America, a restoration movement began to take shape, a movement that emphasizes the systematic self-education of human communities about the habitats that support them.

Homesteaders who tended salmon eggs gained more intimacy with the creatures freshwater needs than any classroom training might have given. Workers replanting barren slopes with local Douglas-fir seedlings and monitoring their survival learned a generation's worth of the processes of natural succession within a few years. Nothing teaches practical hydrology more quickly than attempts to armor eroding stream banks.

Habitat rehabilitation work quickly expanded to include a more informed examination of land-use practices. Organizations like the Institute for Sustainable Forestry developed measurable standards for timber production within ecological parameters. Land trusts were established to move certain lands into the public domain and administer others through benign conservation easements. All these new organizations showered the community with educational newsletters. Collective learning of this sort had not taken the form of social institutions since the destruction of indigenous peoples rituals.

It was trial and error. Like Gil Gregori, a riverfront farmer and urban transplant who has engaged in restoring the Mattole for a quarter century, most settlers didn't arrive with the knowledge that willow plantings will attract valuable insects, shore up banks, and cost less than moving boulders. "I learned it," Gregori says. "(I saw that) they slow the water down. If you can get something to grow there, it's going to do the work for you. As the years went by, people started seeing what was working and what wasn't, which influenced not only the land but their own identity, says Gregori's partner Robie Tenorio. "The restoration feels right," she says. "It feels like you're here, and it's your connection to the land. We live on the river, and this is where we are."

Playing counterpoint to these progressive movements are the various effects of the new-age version of the cash economy- outlaw marijuana production- introduced by the newcomers, but now widespread. Early cash flow from these activities freed up volunteer time that nourished the arts and social and environmental movements. But recent innovations in bunker-style indoor growing powered by large, often unattended, generators are now able to destroy habitat with diesel spills. Community erodes as people hide their daily activities from each other, and generalized paranoia blooms in the form of locked gates and more extreme types of security.

Nonetheless, a community has responded to the land.

In 1988, the Mattole Restoration Council's survey of old growth habitat in the Mattole revealed it had been reduced by 93% since 1947. The survey also revealed that none of the remaining habitat had permanent protection.

A dramatic poster map was mailed to every one of several thousand residents and landowners in the valley. This local information moved community groups to engage in acquisition and regulatory efforts that put some two-thirds of the remaining old forests under public protection by 2000. Maxxam's three thousand acres in the North Fork are the last and most valuable legacy habitat remaining unprotected.

file photo

As I begin writing, a woman named Kim Starr has been sentenced to 120 days in the county jail for defending some of the last of the watershed that looks as it did two hundred years ago. "When that wildness is threatened," Starr said from Humboldt County Correctional Facility, "I donÕt know what else to do. All the waterways and the rolling hills and all the mosses on all the Doug fir trees and bay laurel trees and all the old-growth: That wildness gets in our hearts. It hurts knowing that 60 acres have been just totally stripped in that area."

file photo

Starr is one of several hundred forest activists and several score residents resisting Maxxam"s intention to take down this old forest in the next decade. Her sentence is stiffer because she refused probation. "I reject that system completely," said Starr, who said she wouldn't rule out more civil disobedience. "The more of us that do it, the stronger we become." The 54 people arrested for similar incidents of trespass and resisting arrest (they tend to be locked down and difficult to remove when arrested) await sentencing. Up to 200 additional "John Does" can be charged with obstructing a lawful business as part of a strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP suit) and restraining order begged and received by Pacific Lumber/Maxxam Corporation.

file photo

Two irreconcilable and very modern projections of human desire are encountering each other on these remote lands. The seemingly dominant one, supported by regulations and law, is the treatment of landscapes as sacrifice zones to what Wendell Berry calls the total economy, where there is no value but that measured in dollars. The outcome of this vector of desire is all too predictable, as can be seen in the preceding history.

Resistance to this alternative, at its finest, may be emblematic of our desire to reintegrate human communities and landscapes. Until we learn more about the land's own strategies for recovery, the results of this effort are unpredictable, but the more wild habitat we allow to be destroyed, the less likely it is to reach fruition.

The practitioners of civil disobedience are buying time for community activists to explore acquisition alternatives. By putting their lives on the line for wild, living landscapes, they lend strength to the foresters and landowners, restorationists, and environmentalists who are inventing the details of a livable future. The land demands of us that we develop a long view of the future. If that future is to include the lives of places and of communities of place, we are also required to learn the lessons of our long experience of those places, and learn them soon.

Freeman House, a resident of the Mattole River valley, is author of Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species (1999, Beacon Press, Boston).

This article first appeared in Terrain Magazine Fall 2001. Terrain is the magazine of the Berkeley Ecology Center.

Labels: Ancient Forest, Forest Defense, Homesteaders, Logging, Mattole River, Mattole Valley History, Restoration, Salmon, Sustainability, Threatened Oldgrowth Forest

Old Growth Douglas Fir Forest on the Lower North Fork of the Mattole River.

Old Growth Douglas Fir Forest on the Lower North Fork of the Mattole River. Ancient Forest in Sulpher Creek Headwaters.

Ancient Forest in Sulpher Creek Headwaters.